The churches in the towns of Andahuaylillas and Huaro, along with the Virgen Purificada in Canincunca make up the Ruta Barroco Andino. It is sort of surprising to see such opulent churches is towns such small towns.

Andahuaylillas

The town of Andahuaylillas is situated about an hour south of Cusco in the province of Quispicanchi. Andahuaylillas was founded in 1572 by the Spanish as one of the reducciones that were created to re-settle native populations and facilitate their conversion to Christianity as well as to create a ready supply of easily exploitable labor.

Iglesia de San Pedro, Andahuaylillas

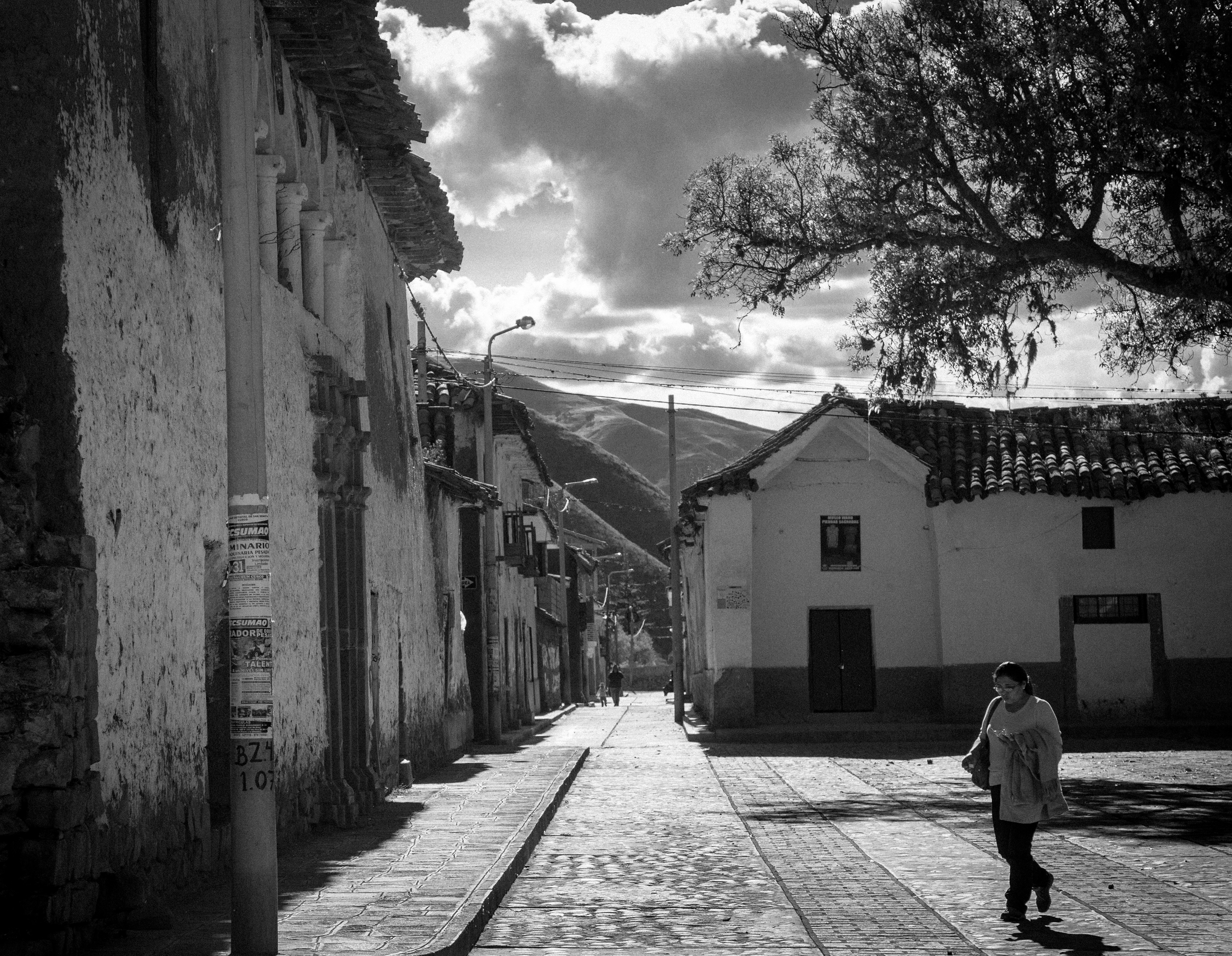

Street corner in Andahuaylillas

After traveling from Puno at over 12,500 feet, Andahuaylillas felt almost tropical at 10,000 ft. The main attraction at Andahuaylillas is the Iglesia de San Pedro. The Jesuits began construction in 1570. The building was completed in 1606.

Ornate entrance to Iglesia de San Pedro, Andahuaylillas

The Iglesia de San Pedro is located on the southwest corner of the Plaza de Armas. It was originally the site of a huaca, or Inca holy site. The Iglesia de San Pedro is known as the Sistine Chapel of the Americas because of the ornate baroque interior. The walls are completely covered with murals and canvases. The altar is most impressive.

Iglesia de San Pedro from the Plaza de Armas

Riaño's Camino al Cielo y Camino al Infrierno. From the blog De Arte y Cultura

Juan Perez de Bocanegra was the parish priest for Andahuaylillas when the church was completed. He was responsible for commissioning Luis de Riaño to paint the impressive murals that adorn the inside walls in the 1620s. Luis de Riaño's most famous mural is the Camino al Cielo y Camino al Infierno which is painted around the main entrance on the inside of the church. The painting depicts the paths to Heaven and Hell.

Baroque interior of the Iglesia de San Pedro. From Ruta Barroca Andina

Many of the paintings incorporate native religious symbols in an effort to evangelize the local population. This is the same reason the church was built on an Inca shrine. Another example of incorporating native symbolism into the church is the very prominent Sun that sits atop the altar. Inti, or the Sun, was one of the primary Inca deities.

Crosses at Iglesia de San Pedro, Andahuaylillas

Huaro

About five minutes south of Andahuaylillas is the town of Huaro. Like Andahuaylillas, Huaro is home to a very ornate baroque church, San Juan Bautista de Huaro. Both towns are located along the Inca road system that went south from Cusco.

San Juan Bautista de Huaro Church in Huaro

San Juan Bautista de Huaro is a Jesuit church that was built in the late 16th century. Murals were painted on the walls and ceiling, new ones often covering older ones. The murals are aimed at explaining the Christian cosmology to the native population and they often incorporated Andean symbols.

San Juan Bautista de Huaro bell tower

Choir loft of the San Juan Bautista church in Huaro. Image from Ruta del Barroca Andina

There are several canvasses on the walls as well that are typical of the Cusco School of painting. The most notable artist whose work is in the church is Tadeo Escalante.

Intricate stone patterns in the plaza in front of the church

Street in Huaro

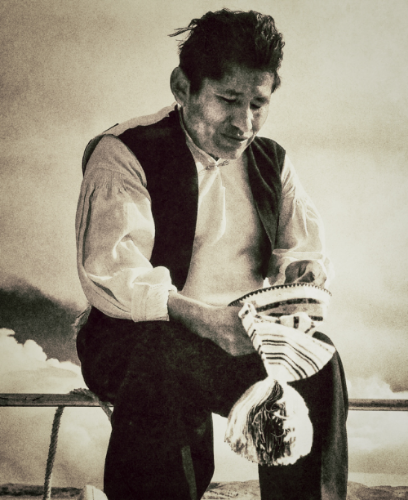

There is a long history of human settlement in the Huaro region. This area was settled by the Wari people long before the Inca and later, the Spanish. The nearby ruins, Pikillaqta or "Flea Town", date to this period. Excavations in Huaro itself also revealed Wari settlements.

San Juan Bautista de Huaro

Both Huaro and Andahuaylillas lie in the Vilcanota River Valley. The Vilcanota ultimately becomes the Urubamba and flows through the Sacred Valley of the Incas, eventually winding around the mountains that kept Machu Picchu hidden for centuries. Huaro and Andahuaylillas are also situated on what was once the main Inca road that led from Cusco to Lake Titicaca. They are very small towns that would be easily overlooked if it weren't for their ornate baroque churches. If you are staying in Cusco, they are well worth a visit. Another way to see them is by using bus services, like the Inka Express, which run between Puno to Cusco, although your time is rather limited in each town.

Building on the Plaza de Armas in Huaro